I'm currently in my final year of The John Lyon School in Harrow. For six hours per week, I have Politics, with the fantastic Mr J Armstrong. You can follow him on Twitter, actually. But the reason I'm mentioning him is that we often have a fascinating discussion on a three-letter suffix, and where it can be applied: "-ism".

I'm currently in my final year of The John Lyon School in Harrow. For six hours per week, I have Politics, with the fantastic Mr J Armstrong. You can follow him on Twitter, actually. But the reason I'm mentioning him is that we often have a fascinating discussion on a three-letter suffix, and where it can be applied: "-ism".

Socialism exists as an ideology, so does Liberalism, and Conservativism. Within these, you have your "sub-ideologies": socialism can be broken down into Marxism (original and orthodox), social democratism, and Blairism; Liberalism can be broken down into Classical Liberalism and Modern Liberalism, as well as neo-Liberalism; Conservativism can be broken down into Traditional Conservativism, One Nation Conservativism, and Thatcherism (or "New Rightism").

Not one person, Left, Right, or centre, would deny that "Thatcherism" is a distinct political ideology, not dissimilar to monetarism. So why doesn't John Major's government get the same treatment? I've only ever seen the term "Majorism" used once by the media, in 2011. However, as I shall now demonstrate, Majorism is clearly a distinct politico-economic ideology. Do I follow it? Not really, I'm more of a Thatcherite.

ECONOMICS

Whilst continuing some Thatcherite economic policies, such as privatisation (such as the 1993 privatisation of the rail network), Major had a economic ideology largely very different to Thatcher, contrary to popular belief.

1 - DEVALUATION

In the aftermath of "Black Wednesday" in 1992, the pound crashed against the Deutschmark, to which it was being pegged after Lawson and Howe bullied Thatcher into going into it in 1989. The Government were forced to take it out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), as it had dropped below its lower limit.

In the aftermath of "Black Wednesday" in 1992, the pound crashed against the Deutschmark, to which it was being pegged after Lawson and Howe bullied Thatcher into going into it in 1989. The Government were forced to take it out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), as it had dropped below its lower limit.

Such a "flash crash" would, surely, cause the pound to go back up soon-ish? No - and with Lamont out of the door, Major decides to adopt an economic policy that is more different than Thatcher's. The pound is kept at a deliberately 'weak' level. What does a weak pound cause? An emphasis - and increases the value of - exports, with the drawback that imports are more expensive. Hence, people stopped importing goods, start exporting them, and we end up with export-led growth.

2 - SMALL GOVERNMENT

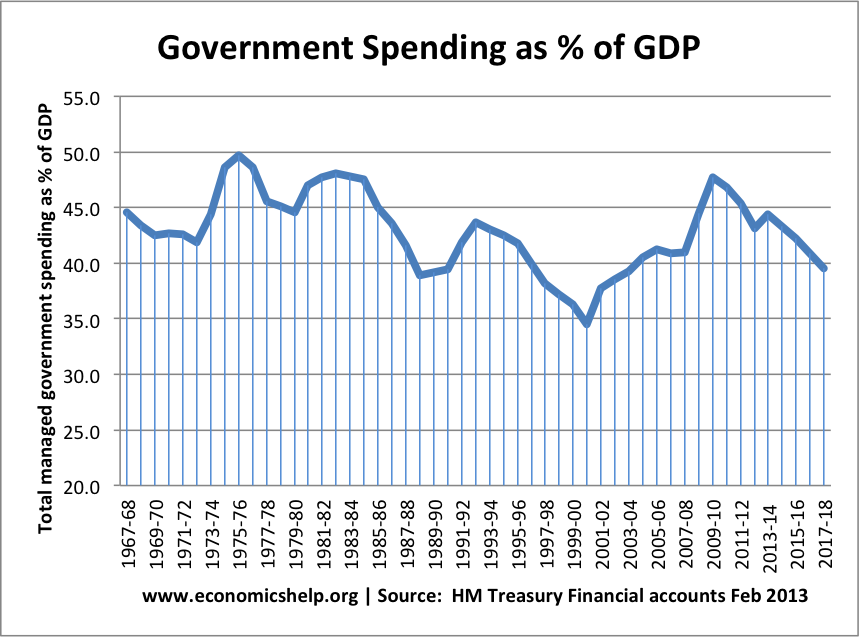

Another key factor of Majorism is to do with budget responsibility. Thatcher did not tend to operate a budget surplus - but after the introduction of Majorism in 1992, the budget deficit does not rise once. With New Labour pledging in 1997 (but not 2001) to stick to the Conservatives' spending plans in this department (and they do stick to their word until the second term), we can attribute the fiscal period of 1993 - 2001 as Majorist economic budget responsibility. The budget deficit does not rise once - by 1998, this even hits a surplus.

By 2001, government spending as a percentage of GDP is at its lowest level since records began - and even the current Conservative government will not get this low (they were on course to, but minor changes to the economic forecast in the March 2015 budget means that they are no longer on course to "beat the record"). Thatcher didn't really decrease government spending as a percentage of GDP in this way.

3 - UNEMPLOYMENT

Thatcher believed in the notion that controlling inflation is more important than controlling unemployment. Whatever your views on this statement, during the Majorism period of 1993 - 2001, save for the introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 1998, unemployment falls at a steady and constant rate. After Chancellor Gordon Brown is no longer bound by the New Labour manifesto to stick to Majorism in 2001, unemployment flattens out. He does this by increasing job opportunities for those out of work - one of the founding principles of the "back to basics" campaign of 1992.

Thatcher believed in the notion that controlling inflation is more important than controlling unemployment. Whatever your views on this statement, during the Majorism period of 1993 - 2001, save for the introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 1998, unemployment falls at a steady and constant rate. After Chancellor Gordon Brown is no longer bound by the New Labour manifesto to stick to Majorism in 2001, unemployment flattens out. He does this by increasing job opportunities for those out of work - one of the founding principles of the "back to basics" campaign of 1992.

4 - INTEREST RATES

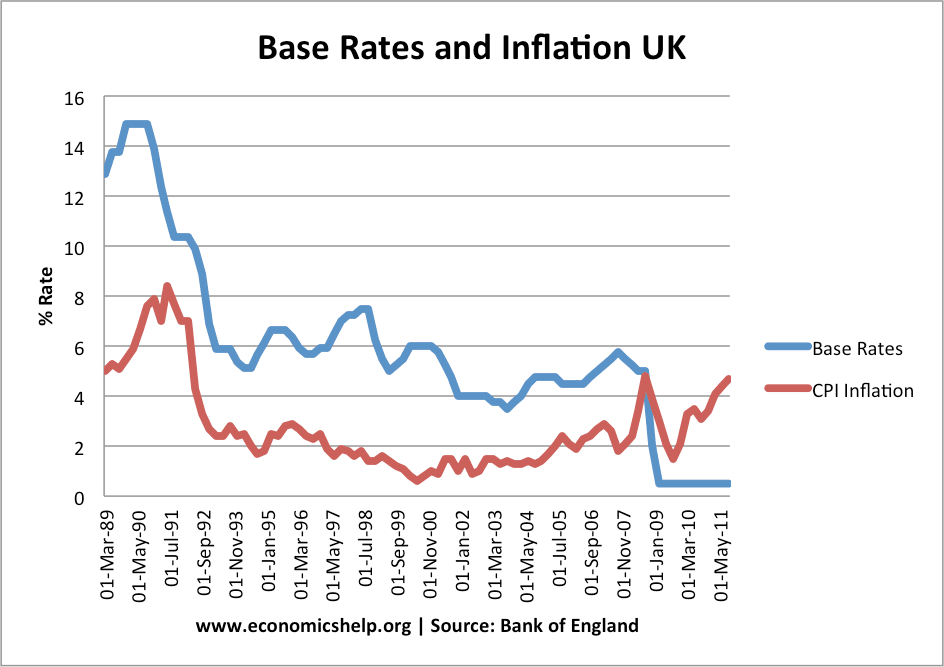

This is difficult to attribute all the way through the 1993 - 2001 period, as the Bank of England became responsible for setting monetary policy in 1997. But even looking between 1993 and 1997, when monetary policy was still within the government's control, the government had more control of interest rates after "Black Wednesday" than it did between 1989 and 1992. Interest rates hit a 20-year low under Majorism, as unlike Thatcher, inflation was not seen as a huge problem. Indeed, from a historical perspective, according to the BBC's "Back In Time For Dinner", the sheer amount of products available in the early 1990s, with a tin of beans being able to be purchased for just 3p, for example, meant that controlling inflation harshly, as had been done right up until 1992, was no longer necessary. Despite this, inflation continued to fall.

This is difficult to attribute all the way through the 1993 - 2001 period, as the Bank of England became responsible for setting monetary policy in 1997. But even looking between 1993 and 1997, when monetary policy was still within the government's control, the government had more control of interest rates after "Black Wednesday" than it did between 1989 and 1992. Interest rates hit a 20-year low under Majorism, as unlike Thatcher, inflation was not seen as a huge problem. Indeed, from a historical perspective, according to the BBC's "Back In Time For Dinner", the sheer amount of products available in the early 1990s, with a tin of beans being able to be purchased for just 3p, for example, meant that controlling inflation harshly, as had been done right up until 1992, was no longer necessary. Despite this, inflation continued to fall.

Whilst being slightly speculatory, it can be argued that the Bank of England adopted Majorism until 2001, too: the range interest rates were in in this period were where they were between 1994 and 1997. Lo and behold: post-2001, they're dropped below their Majorite trough of 5%, and inflation starts rising.

SOFT EUROSCEPTICISM

With the thorny issue of the European Union ripping the Conservative Party to shreds in the late 1980s (taking Thatcher along with it) and early 1990s, John Major attempted to balance the extreme views on both sides of his party by adopting a policy of soft Euroscepticism.

1 - OPT-OUT ON THE SINGLE CURRENCY

John Major was caught between a rock and a hard place when it came to the thorny issue of the Euro; on the one hand, he had Ken Clarke et al - those who wish for full European integration, including the adoption of the single currency, and the Europhiles responsible for driving out Thatcher. On the other hand, he had John Redwood et al - the hard Eurosceptics who didn't want us to go into the single currency, or any single market at all. So when John Major went to Maastricht in 1992 to negotiate and sign the Treaty on the European Union, he declared the opt-out he'd secured on the Euro "game, set, and match for Britain".

John Major was caught between a rock and a hard place when it came to the thorny issue of the Euro; on the one hand, he had Ken Clarke et al - those who wish for full European integration, including the adoption of the single currency, and the Europhiles responsible for driving out Thatcher. On the other hand, he had John Redwood et al - the hard Eurosceptics who didn't want us to go into the single currency, or any single market at all. So when John Major went to Maastricht in 1992 to negotiate and sign the Treaty on the European Union, he declared the opt-out he'd secured on the Euro "game, set, and match for Britain".

2 - VETO

This turned out to be a case of "out of the frying pan, and into the fire", but at the time, he was praised by the Eurosceptics of his party for doing so. After the hated Jacques Delors (who Thatcher repeatedly mocked during her final years) was to be replaced as President of the European Commission, Major vetoed the appointment of Jean-Luc Dehaene, who wanted a European super-state. He was praised for this - but the "out of the frying pan, and into the fire" came when he found out they'd ended up with a clone of him instead, Jacques Santer.

This turned out to be a case of "out of the frying pan, and into the fire", but at the time, he was praised by the Eurosceptics of his party for doing so. After the hated Jacques Delors (who Thatcher repeatedly mocked during her final years) was to be replaced as President of the European Commission, Major vetoed the appointment of Jean-Luc Dehaene, who wanted a European super-state. He was praised for this - but the "out of the frying pan, and into the fire" came when he found out they'd ended up with a clone of him instead, Jacques Santer.

3 - BACK TO THE PARTY

Tony Blair was always very good at being able to turn a soundbite. In 1997, one memorable edition of Prime Minister's Questions featured the quotation of Blair calling Major "weak, weak, weak" on the issue of Europe. But if one watches the full eight minutes, Major easily wins on substance, and says that he will ask his PPCs what the position on the EU should be, unlike Tony Blair, who told his PPCs what to think regarding Europe. Before the "referendum craze" of New Labour, this was as close as it got to the people having a direct say.

Tony Blair was always very good at being able to turn a soundbite. In 1997, one memorable edition of Prime Minister's Questions featured the quotation of Blair calling Major "weak, weak, weak" on the issue of Europe. But if one watches the full eight minutes, Major easily wins on substance, and says that he will ask his PPCs what the position on the EU should be, unlike Tony Blair, who told his PPCs what to think regarding Europe. Before the "referendum craze" of New Labour, this was as close as it got to the people having a direct say.FOREIGN POLICY

There's not really a sub-heading I can use here, as it's very easily summarised: not attempting to take sides in conflicts where Britain is not directly threatened. For example, John Major oversaw the war occurring after the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, culminating in the war in Bosnia & Herzegovina in 1993. Major and his cabinet did not wish to get actively involved in it.

There's not really a sub-heading I can use here, as it's very easily summarised: not attempting to take sides in conflicts where Britain is not directly threatened. For example, John Major oversaw the war occurring after the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, culminating in the war in Bosnia & Herzegovina in 1993. Major and his cabinet did not wish to get actively involved in it.COMPARISONS WITH THE CAMERON GOVERNMENT

1 - ECONOMICS

Many people associate the current Conservative front bench with being Thatcherites - when Majorites is a better description of them economically:

Many people associate the current Conservative front bench with being Thatcherites - when Majorites is a better description of them economically:

- A weaker pound in order to promote export-led growth;

- Driving down the deficit and getting into a budget surplus;

- Driving down unemployment through the Work Programme;

- Record low interest rates alongside low inflation.

2 - EUROPE

- Secured an cut in the EU budget in 2012 in real terms;

- Vetoed a treaty that was against the UK's national interest;

- Given a referendum on Britain's membership of the EU.

3 - FOREIGN POLICY

Cameron's foreign policy is more interventionist than Major's, but less so than Blair's.

_______________________________________________________________________

It is unambiguously clear to me that Majorism, as a distinct political ideology, exists. There are distinct policy ideas when it comes to Politics and Economics - although one does have to attribute that it is hard for him to make sweeping changes, considering he was continuing from a previous Conservative government.

I would argue that David Cameron's Conservative government is a Majorite government, not a Thatcherite one, as I have indicated above. (I may go into further detail on this in a later blog post, but I won't promise anything.)